The authoritarian threat from China might help reinvigorate our belief in democracy, yet it won’t be enough if liberals don’t win the battle of imagination for the future.

It’s an essential feature of human nature to not fully appreciate things that we have and take for granted – and to romanticize the same ones when we don’t. Only after we’ve been tied to our beds with a fever do we truly appreciate our immune system and crave the kind of normal days in which we never think about our health.

A similar dynamic is happening in Europe with our collective attitudes towards democracy and its enabling multilateral institutions, like NATO and the EU. This package of values and institutions have been the democratic world’s immune system, enabling an unprecedented period of transatlantic peace and progress, without people being really aware of their role on a daily basis.

Yet as the democratic backsliding of the past decade has showed, these core pillars have been shaken by reactionary and revisionist illiberal forces – a mix of external authoritarian regimes, or domestic far rights and far lefts.

While the reaction against the post-1989 liberal consensus was inevitable due to failures and normal historical pendulum swings, what has been somewhat surprising in many countries, especially in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), was the lack of zeal in defending liberal democratic values, at least outside certain elite groups.

There’s been plenty of theorizing about why democracy (at least the liberal version of it) is facing popular backlash. Some have focused on the reaction by those on the economic losing end of globalization or political transitions. Others have emphasized the resurgence of identity grievances or the rise of authoritarian powers exporting values of their own. Some now suggest we were wrong to think that the spread of liberal democracy was inevitable, and that its emergence in the West may be a rare historical exception and not the rule.

Yet a key part of the problem seems to have been the very belief that with liberal democracy we’ve reached some kind of linear end point in history – a complacency which constrained the liberal political imagination and its ability to inspire. In one of the best essays of the “quarantine period”, Peter Pomerantsev wrote about how in our “end of history” era, the lack of something to strive towards in effect meant an implosion of progress – that “the only politics that is possible in a futureless, flat world is nostalgic, and the choice is merely what one is nostalgic for.”

The global atrophy and insecurity of liberal imagination ceded ground to reactionary forces looking towards glorified pasts. Most of the political projects undermining democracy – from Putin to Erdogan to Orban – have been attempts to restore wounded national prides, in response to what Krastev and Holmes observed were feelings of inadequacy from failures to imitate the West.

Stripped from their once romantic image, liberal ideals became psychologically unfulfilling and even boring once their imperfections became visible. Yet the bigger problem for many progressives is that they failed to provide compelling practical answers to key concerns, such as inequality or climate change. Some on the left are now convinced that these goals can be achieved more effectively by fighting power structures – from capitalism to patriarchy – even through illiberal means.

The fact that liberals lost the battle of political imagination for the future has been reflected globally, including in Eastern Europe, where many are now looking backwards and/or succumbing to the cynicism of authoritarian hegemonic regimes in China and Russia. The latter stuck around long enough to present themselves as viable alternative models, and have been increasingly assertive in manipulating our grievances with democracy.

A recent poll by the International Republican Institute shows that in vulnerable regions like the Western Balkans, relatively thin majorities continue to see democracy as a preferred governance system (though it’s unclear how many of them think the same about liberal democracy). However, the persistently high popularity of authoritarian countries like China, Russia and Turkey and their increasing influence should be a cause for concern.

While the fight for liberal principles and institutions is no longer inspired by any potent positive vision of the future, the same result might ironically be achieved from the fear and threat presented by the dark authoritarian alternatives.

In some countries there is now already a “backlash to the illiberal backlash”, as the erosion of rights by strongmen once again produces grievances, and the hypocrisy of their rule becomes evident with time. Yet looking towards the future there is an even more important dystopian threat in sight that is already giving pause to many.

The rise of authoritarian China to global superpower status has been associated with great anxiety, if not in emerging democracies where China has brought plenty of resources, then at least in many corners of the West, where it is increasingly seen as a “systemic rival”. Many politicians and thinkers, especially in the U.S, are now even proposing a decoupling from China’s economy and setting the stage for a superpower showdown.

Part of “China anxiety” in the West may partially derive from dangerous nationalist sentiments, as some authors are warning. The creation of “Schmittian” existential enemies in the world stage has been frequently used by Western countries to nurture militarism and curtail freedoms at home.

Yet portraying “China anxiety” as mere scaremongering is an even more naïve and dangerous proposition. It neglects the fact that China is an authoritarian superpower with aspirations to spread its norms and values globally – if not for anything else, then to preserve the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) rule at home – thus making it the most serious global threat to democracy since the Soviet Union.

In that sense, it is completely legitimate for liberals today to raise alarm bells about the severity for the China threat, especially in contexts like CEE and the Balkans, where, as the IRI poll suggests, its investments and actions continue to be seen as benign and not threatening.

The threat presented by China will become an important reflection point on the ills of authoritarianism across emerging democracies. While many today may still find appeal in China’s ability to do things such as building a new hospital in short notice and distributing quick loans, the fact that the CCP has caged millions of Uighur Muslims in concentration camps; built the most sophisticated surveillance state; and is militarizing at a fast speed – these dynamics speak more about the CCP’s vision for the future of the world than anything else.

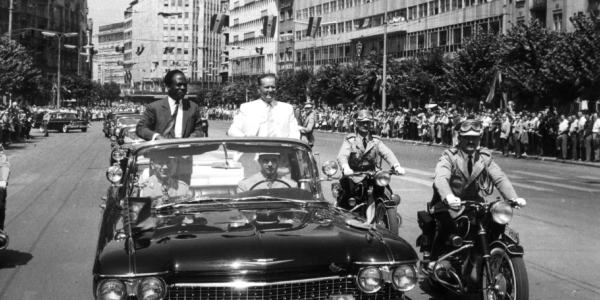

An increased focus and awareness on the threat from authoritarian China would not be the first time that fragile democracies build resilience from a sense of threat. In his fascinating book “Useful Enemies”, Noel Malcolm documents how the perceived existential threat from an encroaching Ottoman Empire played a critical role in the development of early democratic ideas in Western Europe, by providing intellectual elites with a point of comparison and enabling critical introspection of Western society – effectively serving as a sparring partner.

In the cult classic trilogy “Back to the Future”, Marty McFly (played by Michael J. Fox), travels back and forth in time, getting to understand how some undesired outcomes began and trying to change the course of events. We may not have Dr. Brown’s time-travelling car and are limited to act only in the present. But we do have knowledge about our authoritarian past and can use imagination to extrapolate how a future in which the CCP plays a decisive role would look like.

We don’t need to wait for the high-pitch fever to kick-in again in order to appreciate and nurture our immune system. Yet that will not be possible if democratic forces continue to be unable to recapture people’s political imagination with a compelling narrative and vision of the future.