Reclaiming public space in Palermo, Marseille and Prishtina

Life today seems increasingly unpredictable and the current media discourse shows a future threatened by polarisation, climate chaos, rising economic inequality and the impact of the pandemic and the Ukrainian- Russian war. I am writing this essay at a crucial time, for Manifesta, the European nomadic biennial and for our next host city Prishtina, the capital of Kosovo, one of Europe’s youngest sovereign countries. Why is this moment so essential for Manifesta and Prishtina? At present, the Ukrainian-Russian war marks an exceptional geopolitical moment in Europe, as we experience another cruel war on our continent. Putin’s invasion has been condemned globally as the worst violence in Europe since the Second world war. However, we must realise that similar atrocities were committed in Bosnia-Herzegovina thirty years ago, unleashing carnage in Sarajevo, amongst other places. Only twenty-three years ago, NATO intervened in Serbia to put an end to the atrocities in Kosovo. This present moment could not be more crucial in terms of re-imagining the stories of the past that are twined into the future of the Balkans to regain meaning and a sense of the now.

Around the globe, citizens and public administrations are trapped in a shattering experience, as the world becomes increasingly fragmented due to the destruction of the ecologies and social bonds that have enabled humans, to thrive on this planet. However, recent protest movements resist the bewildering condition and discontent with the destruction of nature, culture and everything in-between. From the global Extinction Rebellion and Black Lives Matter protests to the French Yellow Vest movement, a sense of discontent and fear is voiced by citizens. People are critical of the unsustainable growth-and-debt economy and reviving demand for cooperation and shared autonomy. These struggles for equality and direct democracy bring with them the historical perspective that was claimed to have disappeared with the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and which coincided with the inception of Manifesta.

These new activist movements raise my hopes enormously. In this essay, I would like to investigate how they have influenced Manifesta in our past editions as well as in our upcoming edition in Prishtina. Manifesta has always been socially engaged, producing experimental artistic programmes and public events. Born in 1996 in Rotterdam, just after the end of the Cold War that divided the European continent, Manifesta originated from an initiative exploring the histories of contemporary culture in post-communist Europe. Subsequent editions followed in Luxembourg (1998); Ljubljana (2000); Frankfurt (2002); Donostia-San Sebastian (2004); Nicosia (2006); Trentino and South Tyrol (2008); Murcia and Cartagena (2010); Genk (2012); St. Petersburg (2014); Zürich (2016); Palermo (2018), Marseille (2020) and Prishtina (2022), opening this summer.

From Signals to Substance

Nomadic by origin, Manifesta has always adapted itself every two years to new contexts, mapping the geopolitical framework and changing its organisational and artistic models to embed itself into the social and cultural realities of the host cities. Manifesta mobilises local actors, organisations and institutions, investigating and reviving new models of collaboration, co-production, coexistence and cultural policymaking. The recent protests happen in a historically specific moment marked by the new walls that are being built: land walls in the European enclaves in North Africa, Nordic Europe, the Baltic republics and the Balkans; virtual walls, such as biometric border surveillance systems; maritime walls and mental walls, which emerge as a result of rising xenophobia, politics of fear and the increasing securitisation of the European Union[1].

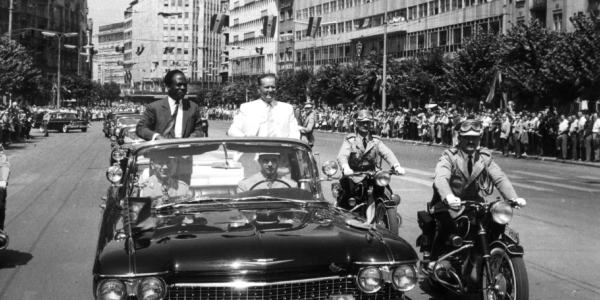

During the preparation for Manifesta 10, in St. Petersburg’s State Hermitage Museum in 2014, repression of dissidents and minorities already increased dramatically when Vladimir Putin implemented the infamous gay propaganda laws. In spring, some months before Manifesta 10 would open, the Ukrainian Revolution caused an unexpected watershed moment and Putin ordered the illegal re-annexation of the Crimean Peninsula in Ukraine, followed by the unlawful war in Donbass. Amid this escalation of violence, Manifesta’s presence in St. Petersburg was highly discussed regarding the critical autonomy of biennials in general. An international group of artists and curators called for a boycott of Manifesta 10, which they argued should not take place in an increasingly despotic Russian state. Despite this specific critique, most political activists in St. Petersburg wanted Manifesta to stay, convinced that the biennial would provide a support structure and a critical platform for Russia’s dissident voices and even be a strategy of resistance.

In the midst of this challenging Manifesta 10 edition, Leoluca Orlando, Palermo’s well-known anti-mafia Mayor, and Andrea Cusumano, Palermo’s Councillor of Culture, expressed their wish to host Manifesta in Palermo in 2018 as an incubator of social change. They hoped Manifesta could become a means for Palermo’s citizens to reclaim their city, which was decaying under the violence of criminal and corrupt systems. I was unsure whether Manifesta’s model, as a travelling organisation commissioning site-specific contemporary art, was equipped to handle such an intricate yet moving request. In response to the challenges in St. Petersburg and the invitation to come to Palermo, I pushed for a transformation of Manifesta, turning the organisation from a monodisciplinary, curated series of art exhibitions into an interdisciplinary, knowledge-and-research-producing platform, focusing on local co-creation rather than international audiences. Manifesta 12 worked with a more inclusive, pragmatic and sustainable methodology to transform Manifesta into a platform of actual substance, offering value to the citizens of the city. From signals to substance thus indicates Manifesta’s aspiration to become a meaningful partner to envision a sustainable and more inclusive society for the citizens of our host cities.

Atlases, Puzzles and Commons: Opening European Horizons

How did Manifesta actually turn signals into substance? Manifesta can be best described as balancing between an autonomous artistic biennial in which symbolic, real-time interventions and aesthetic expressions are produced towards a multi-actor initiative and producing a civic instrument to stimulate citizens to reclaim their city. With the introduction of a pre-biennial urban study functioning as a blueprint for the curatorial team to better understand the context in Manifesta 12, Ippolito Pestellini Laparelli and his team from the Rotterdam-based architecture office OMA were commissioned to conduct an interdisciplinary urban mapping of Palermo, resulting in the Palermo Atlas. The introduction of an urban study had several motivations. It was a direct response to our transformation from an exhibition machine to a urban-focused platform, reacting to a wider discussion of neoliberalism and ownership of cities. It was also a reply to the challenge in Orlando’s invitation, concerning Manifesta 12 as a direct instrument to help the citizens of Palermo to reclaim ownership of their city after 50 years of being occupied by a criminal organisation.

By fusing different specialisations in a multidisciplinary team of creative mediators including journalists, filmmakers, architects and critical theorists and rooting the curatorial effort in holistic urban research, Manifesta 12 tried to extend its impact beyond engaging audiences with contemporary art, to provide Palermo citizens with tools to imagine the future of their city. Thanks to its success, Manifesta 13 presented a study for Marseille, France’s second-largest city: Le Grand Puzzle. The research was commissioned by Manifesta and produced by Winy Maas, MVRDV’s leading architect, and his team from The Why Factory, in collaboration with the National Higher School of Architecture of Marseille, the Marseille-Mediterranean College of Art and Design and the Delft University of Technology. This study of Marseille aimed to achieve stronger and more intimate ties with often invisible communities and mediate their unheard narratives and complex histories of Marseille. The study offered a reflection on this French mainly working-class port city and revealed the city’s possibilities, dreams, necessities and complexities, resulting in a mosaic-like grand puzzle. From these findings, several spatial interventions were suggested, illustrating a path for a new, more inventive sociocultural and geographical way of running the city. Ultimately, Le Grand Puzzle was a tool for citizens to rethink the potential of their city and surrounding area without aspiring a fixed conclusion or singular view of this complex city.

In realising Manifesta 14 Prishtina, we drew on our recent experiences working in Palermo and Marseille. Leaning on lessons learned in those editions while immersing in the conditions of Prishtina, we conceived the urban vision, symbolic interventions, participatory and long-term artistic transformations, and public surveys focusing on the relevance of culture for the wellbeing of communities. The City of Prishtina’s motivation to transform and revitalise public space captivated our team, informing our narratives and practices as well as our capacity-building efforts, especially in education and mediation. For the urban and architectural part, Manifesta 14 was inspired by Turin-based architectural office CRA-Carlo Ratti Associates, our first Creative Mediator. Ratti and his team created an urban vision with MIT Senseable City Lab, based on field research. This vision resulted in the programme pillar Commons Sense, focusing on participatory urbanism to create sustainable urban solutions. Considering Prishtina’s lack of accessible public space, Manifesta 14 is dedicated to creating not only new public spaces but also to reclaim existing and privatised ones, to act as meeting points and incubators of change.

Manifesta 14 is developed through a series of urban interventions, revolving around several sites across Prishtina based on this urban vision, including Grand Hotel Prishtina and a former brick factory. Manifesta invited the citizens of Prishtina in the summer of 2020 to visit and interact with these urban interventions in different areas of the city. The first intervention was at the previously discarded space of the Brick Factory, Prishtina’s most important post-industrial site. By creating an “urban living room”, the intervention triggered a debate about how space can be used, how it can be accessible to the community and how it can become part of the city’s infrastructure.

What the Palermo Atlas, Le Grand Puzzle and Commons Sense show, is how unruly horizontal analyses of uncovered (hi)stories, data-infused facts, myths and fictions can become a horizon to imagine another future for a city. These studies support the claim that contemporary cities around the Mediterranean and in the Western Balkans face ecological crises, but also show that ecologies are increasingly entangled with long histories of social and human conflict, or possibly democratic crises. As a source of data, images, genealogies and stories about the cities, the research creates a “mosaic of fragments and identities emerging out of centuries of encounters and exchanges,” as Ippolito Pestellini Laparelli wrote in the Palermo Atlas. The studies show how the future of a city can be made by civic imagination and courage. I am convinced that our urban studies produce an aesthetic of the real and thus can be considered a form of commonism, as elaborated by Nico Dockx and Pascal Gielen in their introduction to Commonism: A New Aesthetics of the Real. Producing a multiplicity of narratives and a methodical fragmentation of viewpoints on Palermo, Marseille and Prishtina is “a way of thinking of a better, more beautiful world that manifests itself in the liminal zone between fiction and non-fiction, imagination and reality, utopianism and realism,” showing how “fiction can become reality and [how] reality is constructed in the shadows of human imaginations.[2]”

Real for Whom?

Besides Le Grand Puzzle, we introduced another research project in Manifesta 13 to support an inclusive and in-depth study of Marseille. Le Tour de Tous les Possibles brought citizens together to explore alternative means of determining their existence in the city and winning new grounds for solidarity, or unexpected alliances. New possibilities for life in the city have been imagined and formed in more than 22 Citizen Consultations, uniting people from Marseille from all walks of life. Around 500 people from Marseille participated in exchanging and producing alternative narratives and unorthodox ideas and projects, both in live sessions and online. To stimulate discussion, the meetings were based on excerpts from Le Grand Puzzle, inviting citizens to discuss the role that they as individuals together with the city and Europe could play in the transformation of their city.

Developing these citizen workshops for Manifesta 13 Marseille as a form of direct democracy was a response to a series of events taking place in the city. These events related to Marseille’s complex infrastructure and the sometimes precarious living conditions, pollution and mobility issues that are felt in most of Europe’s larger cities. In October 2018, during the preparations for Manifesta 13, the grassroots Yellow Vest movement took shape. In Marseille, a tragedy marked the birth of unprecedented solidarity between citizens. In November 2018, two poorly maintained buildings collapsed on rue d’Aubagne, in the heart of the city, killing eight tenants.[3] In the wake of this tragic event, citizens came together, uniting in various collectives. Our citizen workshops in Marseille, constituted what Jacques Rancière describes as an aesthetic, rhetorical and reasoned “system of self-evident facts of sense perception that simultaneously discloses the existence of something in common and the delimitations that define the respective parts and positions in [the common]”.[4] The encounters took place in prisons, schools, shops and public spaces and made the political join with the social, which according to Antonio Negri is the fundamental concept of an assembly: Now, today, we have the opportunity to transform the assembly into a force. Because that is politics: lending force. Or, that is aesthetics, if one wishes to use that term: lending form and force.[5]

For Manifesta 14 Prishtina, we created cross-sectoral Citizen Consultations in urban and rural areas to understand what people mean by their culture and the relevance of their culture. We translated these findings in our education, artistic and other programmes, but also in the composition of the team, venues and allocation of long-term projects. The future of a city can be created by civic imagination, transformation and courage. This perspective is only functioning by involving diverse communities and the public through a series of activities both in focus groups as well as in quantitative studies. The Open Forum, which we organised in February 2022 to interact with the cultural sector, was an opportunity to collectively explore and reflect with the citizens on the complexity of the cultural landscape of Prishtina.

It is in the pendulum-like swinging between form and force described by Negri that I propose to position Manifesta’s reinvented model, which embraces the sociopolitical movements and divergences found (again) today in our host cities and Europe at large, which in their turn inspired Manifesta’s methodologies that hover between art and sociology. To extensively analyse the conceptual borders and differences between art and sociopolitical structures is in my opinion not appropriate, as they are both aesthetic-constitutive practices. Rather, Manifesta is interested in the synthesis of the collaboration between Manifesta and the public institutions in the host city and its citizens, finding ways to allow the production of artistic and political practices that have become one and many at the same time, showing common ways of working, caring, living and dying in a city.

Programming Alliances

In Marseille, Manifesta’s early collaboration with local partners and citizens also shifted the attention to a different audience. Instead of the international audiences who have traditionally populated the biennial, Manifesta started prioritising the slower, less visually spectacular relationships that can be formed between local communities from the metropole region. This new audience requires alternative forms of mediation and demands more intimate co-productions and structures between Manifesta and the city. This change further amplifies a structure in which several models of artistic programming and engagement function next to each other, opposing any form of hierarchy.

In Prishtina, we abandoned hierarchy by becoming radically local, learning, and giving voice to, the people of Prishtina. There will be no main or parallel programme, but simply stories that explore the different venues, places and histories of the city. Therefore, for the first time, Manifesta has stimulated the inclusion of non-institutional and sub-cultural activists and artivists movements representing the vast amount of Kosovar talent inside the biennial next to multiple series of influential institutions that define Prishtina’s rich and dynamic cultural ecosystem. This means that Kosovar participants are balanced, equally with all other international partners and participants in the biennial, inviting us to develop different modalities of transdisciplinary working in a biennial perspective. Manifesta 14 has also created a regional parcours, connecting the Prishtina programme to regional cultural partners through the Western Balkans Project and establishing a lasting network.

In a changing world, Manifesta is also experimenting with new democratic models of curation. In Marseille, the three-fold Manifesta 13 programme included: an external curated programme with a team of international specialists; a programme to connect local institutions, galleries, artists and curators; and an education and mediation programme. Over the last two years, to create a more tangible legacy for Prishtina, we have been working collectively and closely with Kosovar urbanists, cultural professionals, artists, and thinkers. Focusing on research and knowledge production, Manifesta implemented strategies based on the needs and interests of local communities with an ambition to explore new practices and new ways of learning and unlearning.

The big change I introduced is that we are developing more long-term institutional projects, where Manifesta is the initiator and together with its local team sets up the parameters and transfers the project to those who can maintain it afterwards. So, we still produce artistic projects, but also set up new models of art institutions and of learning, alternative mediation models, and alternatives for mobility and ecological issues. I am inviting for each edition and each issue the best practitioners to create imaginary dreams together. In all these Manifesta cities, communities and citizens are separated from the artistic communities. A big part of our work is to bring these poles together and stimulate them to find new ways to collaborate. A successful project in Marseille was the founding of a community-art centre in a deprived neighbourhood where communities and cultural workers give voice to untold histories, which now turned into a permanent institution.

When preparing for our current edition in Prishtina, I experienced a pressing purpose for Manifesta’s presence in this part of Europe, where we can co-create sustainable projects in areas such as urbanism and ecology as well as increase the standing of interdisciplinary institutions in education initiatives. In this sense, Manifesta has persisted as a platform for experimentation ever since our first edition in Rotterdam in 1996. In Kosovo, numerous long-term projects have been initiated. That is our ambition: to be the incubator and create the conceptual framework while the local community assumes collective ownership and continues after Manifesta 14 will close. One example of such a project is the Green Corridor which will transform a part of the disused Prishtina – Belgrade railway into a new green space and pedestrian path connecting the Brick Factory to the Palace of Youth and Sports in the heart of the city. The community will be involved in the planting, design and maintenance of this corridor. In close collaboration with the public administration, this project will foster long-term environmental change in the city.

In a constantly changing world, Manifesta has rethought and will keep rethinking the model of the biennial on several levels, relating to the origin of our structure, namely nomadic, itinerant, and acting as an incubator. In Prishtina, this means changing our knowledge production into a form of participatory practice, next to creating a more tangible legacy for the city and its communities in the form of a permanent interdisciplinary institution which could be an example of the development of Prishtina’s cultural ecosystem. Sketched out by Manifesta’s artists, cultural practitioners and architects in the many different stories, plays and plots, I rather see the common horizon, with Manifesta as a temporary funambule, and the citizens as the true owners and caretakers of their public space, institutions and cities. Much like this acrobatic tightrope walker, Manifesta shows alternatives in the important, but often difficult task of building diversified alliances, where worlding is a relation based on solidarity and productive collaborations, besides pointing out the ways to promote coexistence. Not only is it essential to ask who owns our cities; we should also imagine how to remember, activate and support each other in our cities.

[1] Member states of the European Union and the Schengen area have constructed almost 1,000 km of walls, the equivalent of more than six times the total length of the Berlin Wall, since the nineties to prevent displaced people migrating into Europe. Source: Ainhoa Ruiz Benedicto and Pere Brunet. ‘Building Walls: Fear and Securitization in the European Union’ in Centre Del.s d’Estudis per la Pau (2018).

[2] Dockx, Nico & Gielen, Pascal. ‘Introduction: Ideology & Aesthetics of the Real’ in Commonism: A New Aesthetics of the Real. Amsterdam: Valiz (2018). p.58-59.

[3] ‘“Ni oubli ni pardon”. Marseille, un an apr.s le drame de la rue d’Aubagne’ in Le Monde (2019).

[4] Rancière, Jacques. The Politics of Aesthetics. London: Continuum (2006), p.12.

[5] Negri, Antonio. ‘The Salt of the Earth: On Commonism. An Interview with Antonio Negri’ in Commonism: A New Aesthetics of the Real. Gielen, Pascal & Lavaert, Sonja (eds.). Amsterdam: Valiz (2018). p.98.