Since the end of the war in 1999, Kosovo has undergone a profound transition. Emerging from the damages of war and ethnic cleansing, the country embarked on a path toward reconstruction, state-building, and ultimately, independence.

However, the declaration of independence marked the beginning of a new set of challenges as the newly independent country faced major internal and external issues. Despite these obstacles, Kosovo has demonstrated remarkable resilience, achieving notable progress in building its institutions, establishing democratic governance, pursuing economic advancement, and achieving global recognition.

This progress has been facilitated by substantial support and assistance from Western allies, particularly the European Union and the United States. However, persisting challenges underscore the ongoing struggle for Kosovo's international recognition and integration in intergovernmental organizations, highlighting the crucial role of effective leadership in achieving its state objectives amid an increasingly complex geopolitical landscape.

Year zero for Kosovo

The aftermath of war and ethnic cleansing marked a pivotal moment for Kosovo. In 1999, as Yugoslav forces withdrew, NATO troops moved in. For Kosovo’s Albanian majority, 1999 became “year zero,” signaling a long-awaited new beginning of newfound freedoms and liberties.

However, this temporary euphoria gave way to the harsh realities of post-war consequences. Many families were left fragmented with some still searching for loved ones in mass graves. Burned homes, destroyed infrastructure and poor living conditions made it difficult to recover from the traumatic effects of war.

Amid these challenges, international investment in Kosovo's reconstruction led to the establishment of a UN-run enclave. United Nations Resolution 1244 established an international presence in the country, creating an amalgamation of different organizations to ensure peace, stability and order. The United Nations Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) was tasked with organizing provisional institutions, while the Kosovo Force (KFOR) provided security.

According to former U.S. diplomat James Dobbins et al., “the U.S. and its allies have put 25 times more money and 50 times more troops, on a per capita basis, into post-conflict Kosovo than into post-conflict Afghanistan.” This increased investment played a crucial role in driving the development of democratic institutions, driving social change and fostering economic growth in Kosovo. Moreover, Kosovo’s small territory and population as well as the citizens’ willingness to embrace change, increased the chances for success.

Kosovo lacked a robust state bureaucracy and UNMIK was crucial in assisting Kosovo establish its institutions. Within a few years, Kosovo had developed systems for taxation, fiscal policy, governance, education and healthcare, among others. In this context, UNMIK was welcomed with optimism by local Albanians, who viewed the mission as a symbol of the old regime’s departure and as the vehicle towards state-building and independence.

Path to independence

In the subsequent years, the people of Kosovo became more insistent on having greater control over their own destiny, with their primary goal being full independence. As talks about Kosovo's final status stalled, Kosovo Albanians became increasingly doubtful of UNMIK's effectiveness, leading to growing frustration over the prolonged political uncertainty. To the Kosovo Albanian majority, UNMIK became the main barrier to achieving independence.

Consequently, UN-led decentralization talks (otherwise known as the Vienna Negotiations), led by former Finnish President, Martti Ahtisaari, began in 2006 to discuss the future status of Kosovo. Kosovo sought full independence, while Serbia insisted that Kosovo remain an autonomous region within Serbia.

In March 2007, Ahtisaari concluded that the “only viable option for Kosovo is independence” and suggested an initial period of supervised independence. Ahtisaari developed a comprehensive package of measures to protect and promote the minority rights of non-Albanian communities in Kosovo.

Even though his plan was rejected by Serbia, it represented a contribution to peace and coexistence. The Ahtisaari Plan was not endorsed by the UN Security Council due to Russia’s veto. However, it became evident that Kosovo’s path to independence would become a reality without the approval of the UN Security Council.

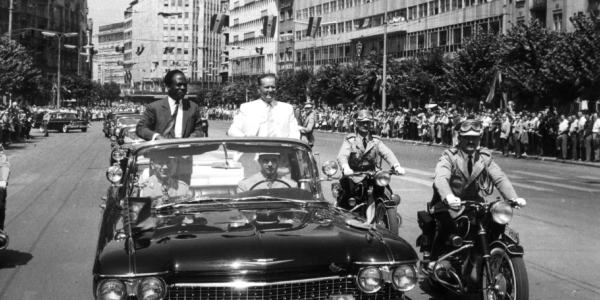

Three months later, U.S. President George W. Bush made a historic visit to Albania, the first-ever U.S. president to visit the country. During his visit, President Bush stated: “At some point in time, sooner rather than later, you have got to say enough is enough. Kosovo is independent and that is the position we have taken.” This statement by the U.S. president was largely seen as a strong signal of support for Kosovo which then took important steps towards independence in the following months.

Kosovo declared independence on February 17, 2008. Even though the independence of the newborn state was swiftly recognized by the majority of democratic nations, it faced challenges of governance and lacked international recognition from other states, raising doubts about its legitimacy.

The quest for international recognition and legitimacy

The declaration of independence marked the beginning of an arduous journey toward establishing a well-functioning society founded on the principles of democracy and the rule of law. Kosovo faced additional hurdles from countries such as Serbia, Russia and China, which vehemently opposed its statehood and blocked its membership in prominent intergovernmental organizations such as the United Nations and Interpol.

Today, Kosovo remains only partially recognized and its international position is severely impacted by its relationship with Serbia. Despite over a decade-long process by the EU to normalize relations, a definitive solution remains elusive. The lack of a final resolution with Serbia has impeded Kosovo’s potential for greater growth and development.

In addition, the lack of recognition from five EU countries (Cyprus, Greece, Romania, Slovakia and Spain) and four NATO member states (Greece, Romania, Slovakia and Spain) poses a problem for Kosovo’s Euro-Atlantic aspirations.

Progress amid struggles

Despite such major hurdles, Kosovo has demonstrated remarkable resilience, surpassing expectations with its achievements.

Kosovo has managed to gain more than 100 state recognitions and has become a member of prominent international bodies and organizations including the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, Central European Free Trade Agreement, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, and various international sports federations.

Nevertheless, the ongoing struggle for international recognition and legitimacy remains a formidable obstacle, posing a serious challenge to the country’s potential for further development.

This has not been an easy process, especially taking into account that Serbia considers Kosovo an integral part of its territory, continues to deny its genocidal past and has not shown empathy for the war crimes committed in Kosovo. Furthermore, Serbia continues to oppose Kosovo’s quest for international recognition and uses every opportunity to block its path.

Despite facing challenges such as high corruption and political interference in the judicial system, environmental pollution and challenges in accessing quality healthcare and education – Kosovo has also made substantial advancements post-independence, performing better than most countries in the Western Balkans on important international indexes such as the rule of law, media freedom, state of democracy and corruption perception, among others.

Kosovo has championed the organization of free and fair elections, providing preliminary results in a matter of hours after elections. The country benefits from a vibrant civil society and independent media which continue to serve as crucial actors to safeguard and promote democracy and advocate for human rights.

Although Kosovo is a developing economy, the country has managed to maintain a relatively stable economy with an average of 4% economic growth. The standard of living has increased significantly and unemployment rates have decreased. For example, in 2014, Kosovo’s unemployment was remarkably high at 35%; today, it stands at around 12%.

In 2018, the Kosovo Assembly passed legislation that transformed the Kosovo Security Force (KSF) into a conventional army, beginning a decade-long process to achieve full military capacities and capabilities. Ever since, the KSF participants regularly participate in NATO military drills, with the most prominent one being Defender Europe. The KSF made history in 2021, dispatching its first-ever peacekeeping mission in Kuwait alongside U.S. National Guard troops from the state of Iowa.

While Kosovo is far from a fully-fledged democracy and many challenges persist, looking 25 years back, Kosovo’s progress is undeniable. Emerging from the ruins of war, Kosovo remains a rare success story of state-building, establishing a functioning liberal democracy with a clear Euro-Atlantic foreign policy orientation.