“The Other Serbia” project has compiled a collection of the thinking of Serbian intellectuals who opposed the Serbian authorities’ severe violations of the human rights of Albanians in Kosovo in the period from Serbia’s abolition of Kosovo’s autonomy, on 23 March 1989, to NATO’s entry into Kosovo on 12 June 1999, and later still. These violations reached their culmination in 1998 and 1999 with the killing of almost 10,000 Albanian civilians, the raping of thousands of women, the deportation or displacement of almost one million Albanians, and the burning and destruction of 100,000 homes, buildings, and heritage sites.

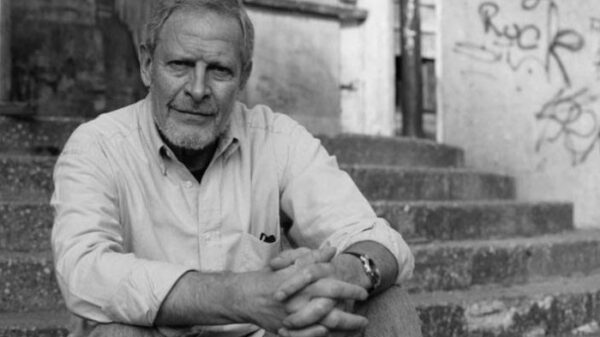

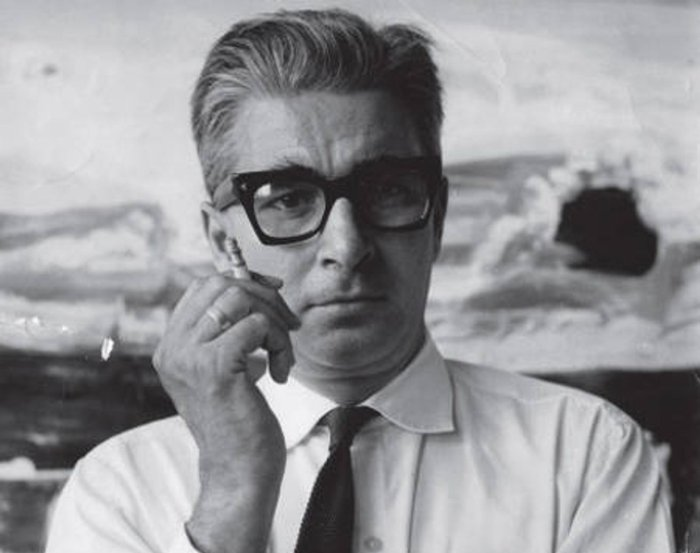

In “The Other Serbia” project, we have extensively researched articles and interviews published over three decades in the daily press and weekly publications in Kosovo, Serbia and further afield. This volume includes excerpts from the articles and interviews of the most prominent of these intellectuals, the architect Bogdan Bogdanović [1922–2010], in which he talks about the brutal violation of the human rights of Albanians in Kosovo in the 1990s. In addition, we thought it was important to include excerpts in which Bogdanović provides his views not only on the independence of Kosovo and its relations with Serbia, but also on the overall relations between Albanians and Serbs.

In one of the interviews, Bogdan Bogdanović reveals how, in the late ‘80s, as he was returning from Mitrovica to Belgrade with an Albanian driver in a car with Mitrovica plates, he understood what it meant to be Albanian in Yugoslavia: “People were merciless with us along the road – cursing at us, whistling, threatening to run us over with a truck.” Regarding the situation of Albanians in Kosovo in the early ‘90s, Bogdanović remembers how a Serbian police officer told him: “You have no idea what our police officers are doing in Kosovo.” He labeled Serbia’s intensifying repression and apartheid in Kosovo during the ‘90s as fascism, adding that this is something that “the Serbian people, us Serbs, our children, and grandchildren will carry on our conscience.”

Concerning the myth that Kosovo was the cradle of the Serbian kingdom in the Middle Ages, Bogdanović states that at that time, Belgrade belonged to the Hungarians. He did not support the Serbs complaining that the demographic situation in Kosovo was changing with the increase in the Albanian population. His argument was that Serbs have been leaving Kosovo for the hundred years it was part of Serbia, and one reason for this was moving to wealthier areas, selling land to Albanians at very favorable prices. He claimed that since about 2 million Albanians, comprising over 90% of the population, live in Kosovo, Kosovo belongs to those who live there, and this should be communicated to the Serbian people, even though, as he claims, everyone already knows it but lacks the strength and courage to admit it. Moreover, Bogdanović would often say something that sounded a bit like bartering at a flea market: “...we’ve made ourselves a good deal because we gave away Kosovo, but we got Vojvodina.”

Bogdanović emphasized that the Serbian people should be made aware that in Kosovo, the Serbian heritage will truly remain and Serbian monasteries will persist, since even Greek temples are mostly located outside of Greece, in the Middle East, from Alexandria to Serbia. He was convinced that had Serbia not committed evil doings to the Albanians, the latter would preserve the Serbian heritage in Kosovo, and perhaps a solution similar to Mount Athos would have been found. Moreover, Bogdanović referred to stories about how Albanians actually preserved these temples, such as the Patriarchate of Peć which was protected by the Kelmends from Rugova.

Bogdanović opposed the double standards of representatives of the Serbian regime in the ‘90s, who sought autonomy for Krajina in Croatia with the right to secede while categorically denying the same right in Kosovo. He was the first Serb to publicly state in 1990 that it was already too late for a republic in Kosovo, even considering the right and desire of local Albanians for unification with Albania as legitimate. According to him, the sooner Kosovo separates from Serbia, the better for modern Serbia because the Kosovo ingrained in the Serbian consciousness does not align with the modern world.

Bogdanović is one of the most unusual Serbian patriots because he worries about the fate of his people and their tragedy. He feels deep pain because heartless, aggressive and criminal politicians have put all that horror on his people’s conscience, committing serious crimes against other nations around, especially against the Albanians. He perceives the fate of the Serbian people during the ‘90s as very dark, and he sees the wars Serbia waged in that period not as military victories or political superiority but ‘as a moral, even mental catastrophe for the Serbian people.’

Among the components of the Serbian national interest, Bogdanović considers friendship with Albanians, preserving the Serbian population that wants to live in Kosovo, and safeguarding Serbian monuments in Kosovo. His patriotism is also evident in his stance that if he had to live in a Greater Serbia resembling the Middle East or a Little Serbia resembling Switzerland, he would always choose Little Serbia.

His opposition to Serbian nationalism is best illustrated by a lengthy letter he sent to Milošević in the late ‘80s. This letter and other anti‒nationalist criticisms directed at Milošević prompted numerous attempts of breaking into his apartment, death threats, and eventually his expulsion from the party. The attacks forced him to move to Vienna in 1993 with his wife Ksenija, where he passed away in 2010.

Bogdanović made several accurate predictions about political events during the ‘90s, even years before they occurred. Three of them are particularly significant: first, that President of FR Yugoslavia Slobodan Milošević would end up in the dock as he would have to answer to many nations, especially the Albanians, for the killed victims; second, if the Serbian people went to war in Kosovo, they would shamefully lose it; and third, as a result of the warmongering policy, Belgrade would be bombed.

Bogdanović attributed the responsibility for the Serbian national catastrophe – how the Serbian nation became so disliked and surrounded by enemies – to the intellectual elite. According to him, this elite failed to teach the Serbian people how to love and did not convey the message that we live in a diverse world, and that we should be happy about it because we coexist with different cultures. Therefore, he consistently urged the Serbs to understand that winning friends is more important than conquering territories. He suggested that the entire strength, intellect, will, and intuition of the Serbian people should focus on friendly relations with the Albanians, but for this you would need a Serbian Charles de Gaulle. After the devastation of cities and the loss of lives during the Kosovo War (1998-1999), he hoped for the awakening of Serbian consciousness. The fact that this did not happen was a source of great suffering for him, and he considered it a moral tragedy for the Serbian people.

After the publication of the thoughts of the intellectual Bogdan Bogdanović, within the "Other Serbia" project, fragments from articles and interviews of several other Serbian intellectuals are included, such as: Miloš Minić [1914–2003], Srđa Popović [1937–2013], Lazar Stojanović [1944–2017], Bogdan Denitch [1929–2016], Ilija Đukić [1930–2002], Ivan Đurić [1947–1997], Mihajlo Mihajlov [1934–2010], Mirko Kovač [1938–2013], and others.

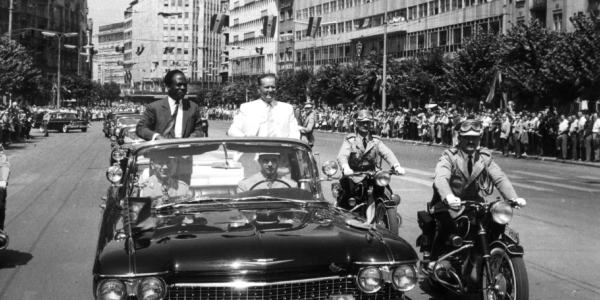

All these intellectuals were inspired by Serbian social-democrats such as Dimitrije Tucović, Kosta Novaković, Dušan Popović, Dragiša Lapčević, Triša Kaclerović, and others. Between 1912 and 1913, when Serbia occupied Kosovo, they opposed the horrendous crimes perpetrated by the Serbian state on the innocent civilian Albanian population there. An article by the social-democrat Tucović in the Belgrade socialist paper of the time, Radničke novine, illustrates this: “...we attempted a premeditated murder of a whole nation.” An editorial in the paper stated that it possessed data on crimes by Serb forces against the Albanians so horrendous that they chose not to publish them. Unfortunately, these crimes were repeated: at the end of the World War I, in 1918 and 1919; then in the period between the two World Wars; at the end of the World War II (1944-1945); between 1946-1966; and finally in the last decade of the 20th century (1989-1999).

Unfortunately, these personalities of the Serbian people have been seen as traitors, they have been prejudiced, anathema and attacked, while the Albanian people have been viewed with distrust and therefore ignored.

Postwar Kosovo does not have a street, square or school named after the lawyer and humanitarian Lazar Stojanović, even though he strongly opposed the state terror of the Milošević regime at the start of the ’90s. Although he was the first and most vociferous intellectual who not only opposed the occupation of Kosovo by the Serbian regime but also supported the independence of Kosovo, the Kosovo Assembly failed to invite him to the ceremony of the Declaration of Independence on 17 February 2008.