Belgrade entered the new year in an unusual manner. Instead of celebrations in main public squares with concerts and mulled wine, thousands of protesters marked the beginning of 2025 in silence.

At 23:52 on New Year’s Eve, students of the University of Belgrade decided to postpone celebrations by organizing a 15-minute moment of silence to honor the 15 victims killed in the collapse of the canopy at the main railway station in Novi Sad, Serbia’s second-largest city.

On November 1, 2024, the newly renovated railway station’s canopy collapsed at 11:52, killing 15 people. The railway station had recently reopened after three years of reconstruction.

The tragedy shocked the nation, sparking widespread anger and disbelief that such a catastrophic failure could occur in a newly renovated facility.

Commemorating the Victims Through Protest

The first wave of protests started on November 5, 2024, students in Novi Sad began organizing weekly protests to commemorate the victims and demand accountability from the government.

Soon, students in Belgrade joined their peers in solidarity. Every Friday, students gathered in squares and streets of Belgrade, stopping traffic and calling for an independent investigation.

The protests rapidly gained momentum, spreading to other cities. At precisely 11:52 each day (the time the canopy collapsed) citizens across the country paused for a 15-minute silent protest to honor the 15 victims. By late November, much of Serbia was effectively paralyzed for 15 minutes daily.

The protests culminated in a massive demonstration on December 23 in Belgrade, where more than 100,000 people gathered. This was the largest protest in Serbia since October 5, 2000, and it sent shockwaves through the government of Prime Minister Milos Vucevic.

Government’s Unsuccessful Attempts to Contain the Protests

The ruling Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) attempted to counter the protests by deploying a high-ranking party members and city officials to disrupt and provoke the protestors. However, the students remained composed, refusing to allow the situation to escalate. Their resilience prevented SNS supporters from compromising the movement.

Facing widespread public dissatisfaction, the government’s initial response consisted of reactive crisis management. The first reaction from the Serbian Government came with the resignation of the Minister of Construction, Transportation and Infrastructure, Goran Vesic after being summoned from the public prosecutor. However, this did not dispel the doubt among citizens and protests continued.

A few weeks later, Minister of Internal and Foreign Trade, Tomislav Momirovic, and the Director of the Public Enterprise Infrastructure of Serbian Railways, Jelena Tanaskovic. Despite these resignations, protests persisted through the end of 2024.

In a bid to calm the unrest, President Aleksandar Vucic was forced to take the center stage. At December 11 press conference he announced several measures, including the publication of documents related to the railway station’s renovation and a 20% budget increase for universities. However, the protestors didn’t budge, claiming that only a third of the documents were made public by the government, leaving the most important ones undisclosed.

By December, 84 of Serbia’s 112 faculties across seven universities were under blockade, effectively halting classes and examinations. High school students also began joining the movement, further pressuring the government.

President Vucic attempted one more time to calm the protestors by announcing a grand scheme of state subsidies for young people to buy apartments and houses. Furthermore, Prime Minister Vucevic announced plans to restructure the government. However, both attempts to quell public outrage failed with protesters rejected both proposals as an attempt to buy their silence.

What makes this protest unique?

Interestingly enough, all measures introduced and adopted by the government, be it real actions or PR stunts, failed to yield results. Even attempts to divide and destroy the protest from the inside, a tactic that ruined many protests in the past, failed. The key reason for this lies in the fact that students also have a very good strategy.

First, they make decisions by utilizing direct democracy – student plenums. As a result, they do not have leaders who can be intimidated or ‘bought’ by the government (although the government is doing its best to scare individuals using the secret service). Second, they have clearly formulated demands, and they do not give up on them, nor do they want to negotiate.

Refusing to meet with the Chief Public Prosecutor has brought even more support to the students. Students do not want to compromise on their requests, which is full transparency of all documents and investigation of all included in the corruption which led to the fall of the railway station canopy.

However, fulfilment of this demand would likely lead towards the top of the political pyramid in Serbia – Prime Minister Milos Vucevic, who was mayor of Novi Sad at the time of the reconstruction of the railway station, and maybe even President Vucic, since Jelena Tanasijevic already stated in her testimony to the prosecution, that the condition for her to take the position of the Director of the PE Infrastructure of Serbian Railways set out by the then minister Vesic, was that she would not have a say in this infrastructural project, since those are negotiated and agreed by Minister Vesic and President Vucic directly.

Could This Be the Beginning of the End for SNS and Vucic?

The tragic collapse of Novi Sad’s railway station canopy and the ensuing protests have undoubtedly delivered the most significant blow to the SNS since it assumed power in 2012.

The citizens of Serbia have endured years of SNS ruling that has pushed Serbia into an authoritarian trajectory, diminishing the opposition, civil society and media. The citizens are also upset with corruption and criminal scandals surrounding the ruling party. Years of disappointment accumulated with the tragedy in Novi Sad, pushing tens of thousands of people to the streets in protest.

Thus, despite the government's efforts to suppress the protests by promises, the protests continue to grow in size and popularity. Spearheaded by students, the movement draws on a historical precedent, as students have often been at the forefront of transformative political changes in Serbia.

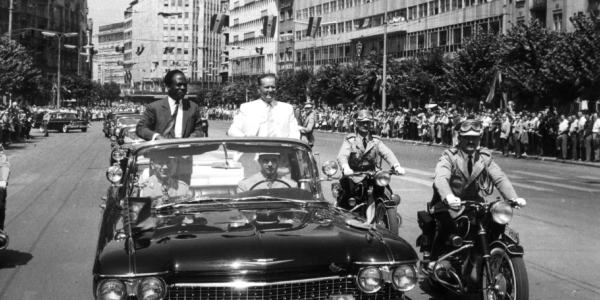

The last time Serbian citizens mobilized in six-digit numbers, their protests led to the fall of Slobodan Milosevic's regime. Could this wave of protests similarly mark the end of the SNS and Vucic’s rule? Only time will tell.