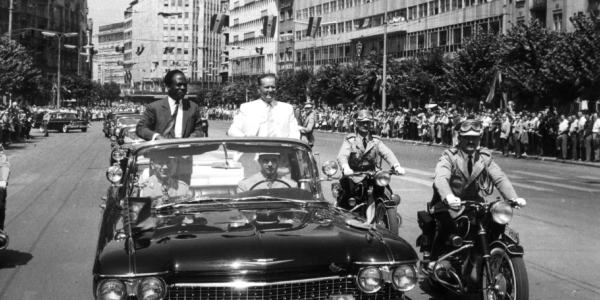

Tony Blair was not in Kosovo for the 25th anniversary of Ferizaj’s liberation on June 12, when a statue of him was unveiled on the boulevard named after the former British Prime Minister. However, following the news about the ceremony held under the scorching sun, a debate erupted on social media regarding the statue. During its casting in bronze, the sculptor was visited by journalists from major international media outlets, such as Reuters, to showcase to the world that Kosovo was honoring Blair for his crucial role during NATO's bombings against former Yugoslavia. While critics on social media questioned the statue’s resemblance to Blair’s actual image, the British newspaper "The Independent" wrote on June 13 that people were convinced the statue of "Tonibler" in Kosovo looked like Jason Donovan, the Australian star of "Neighbours."

“The former prime minister was in attendance at the unveiling on Blair Boulevard, and addressed MPs in a special session in Kosovo’s parliament,” read the second paragraph of the article, even though only a letter from Blair, sent to the statue's initiators, was read at the ceremony. It’s clear that the renowned British newspaper had not verified the timing of Blair’s visit or his absence from the event.

Similar inaccuracies are often found in traditional serious media, which, in the era of technological revolution and fierce online competition, fall into the trap of unverified news due to the speed at which news is delivered. Naturally, serious media outlets correct such unintentional errors, but false news continues to challenge even the most developed societies with a strong press tradition, like the United Kingdom and the United States.

Back in 2017, British MPs established a group that had previously expressed concerns about the impact of fake news, fearing it could become a threat to democracy. The investigative group, founded by the Media, Culture, and Sport Committee of the House of Commons, aimed to define what constitutes fake news and identify the potential impact of its spread within the United Kingdom. However, the spread of deliberate political falsehoods shows no signs of stopping, as technology continues to rapidly advance.

“It will also examine whether search engines and social media companies, such as Google, Twitter and Facebook, need to take more of a responsibility in controlling fake news, and whether the selling and placing of advertising on websites has encouraged its growth”, the British newspaper "The Guardian" reported. The rise of Donald Trump to the presidency of the United States in 2016 only further emboldened populist politicians to deliberately use fake news to gain more votes. This occurred at a time when the far-right began targeting large groups of citizens in Western countries, using racist language and issuing warnings about the expulsion of Europeans with diverse ethnic and religious backgrounds.

The world continues to grapple with the significant challenges posed by fake news, as the reach and influence of social media continue to expand. This year, the stakes are especially high, with billions of people heading to the polls across the globe. As demonstrated by serious investigations in the United States into Russia's influence on the 2016 elections, the actors behind fake news are often organized state mechanisms conducting massive operations, capitalizing on technological advancements in artificial intelligence. They also exploit the lack of national and international regulations against misinformation on social media.

"Billions of people will vote in major elections this year — around half of the global population, by some estimates — in one of the largest and most consequential democratic exercises in living memory. The results will affect how the world is run for decades to come," warns "New York Times" as it analyzes the impact of disinformation on major electoral processes. The New York newspaper also raises the alarm that false narratives and conspiracy theories have taken on the proportions of a global menace on the rise. "Baseless claims of election rigging have undermined trust in democracy," it cautions.

Public relations experts say that foreign influence campaigns are deepening internal polarizing challenges, while also increasingly leveraging the capabilities of artificial intelligence to create false realities. Virtual search giants continue to face accusations of weakening safeguards when it comes to malicious campaigns during election times.

“Almost every democracy is under pressure regardless of technology,” says Darrel M. West, a Brookings Institution expert, adding in the NYT that disinformation campaigns only increase the opportunities for political malice and ill intent against local, central, or supranational powers.

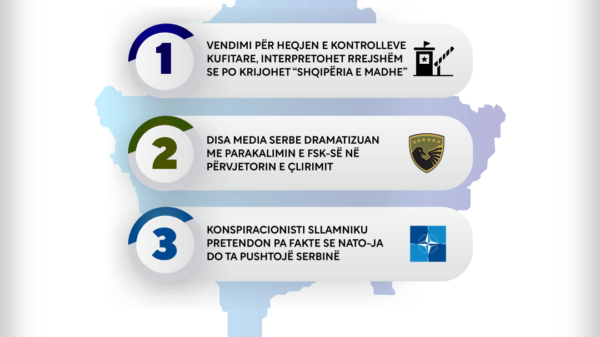

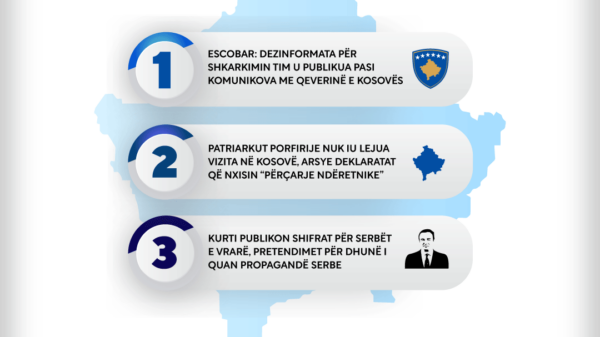

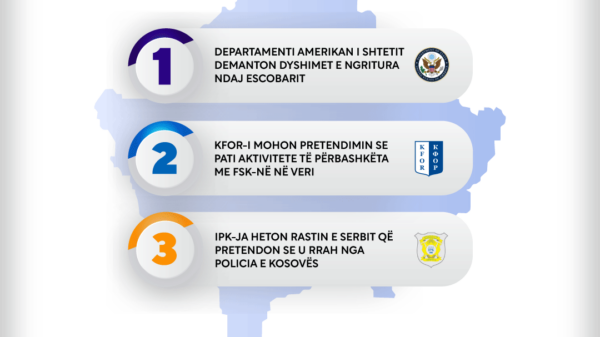

While societies with strong democratic and legal traditions and institutions struggle with fake news and disinformation campaigns, this ongoing battle is far more challenging for countries with young and developing democracies, like Kosovo. Disinformation campaigns are often fueled and funded by powerful groups and individuals within political parties, with leadership silently approving them despite their long-term risks. These campaigns are driven by pseudo-portals and anonymous social media accounts, whose operators remain unknown. These individuals are notably creative in their approach to spreading misinformation! They use city names with added terms like "press" or "info" to present themselves as serious news outlets, where people are personally and family-wise denigrated during debates and critical political decisions—important for citizens but lacking any substantive, well-argued discussion. These are virtual tools that smear not only opposition members but also those who think differently within the ruling party or coalition, whether at the local or central government level. They publish unfounded accusations, touching on sensitive issues such as war values or allegedly questionable patriotic pasts.

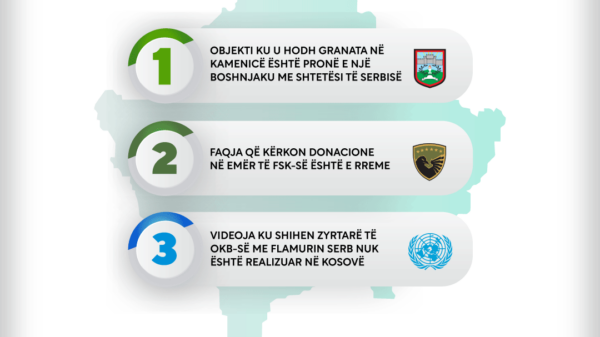

"The Vortex of Lies," as titled in the 2023 report by the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN), also describes the disinformation narratives that have spread in Kosovo in recent years. The report, funded by the European Union in Kosovo, not only fact-checks disinformation campaigns across various fields but also concludes that during a social experiment, the fragility and lack of basic knowledge regarding the safe consumption of information among public officials were evident. The authors find it alarming that a significant number of public officials believed the false information during the social experiment.

“The overall data is concerning, particularly the fact that a large number of officials would disseminate information to others or even spread it without verifying it,” states "The Vortex of Lies." “This study highlights the need to promote media literacy and critical thinking skills to prevent the spread of disinformation.”

Previous experience with misleading news shows that this education must be comprehensive. Among the main recommendations in the "Vortex of Lies" report is the necessity for media to fact-check before publication. The report also calls for building public resilience against disinformation and strengthening the capacities of media regulatory bodies. “State institutions should also enhance their skills and develop strategies to counteract information campaigns against Kosovo.”

The lecturers from the Department of Journalism at the University of Prishtina have been running a voluntary campaign for some time to persuade the Ministry of Education to include media literacy as a mandatory subject. This push is driven by the lack of professional competence among civic education teachers to address misinformation and media issues. When considered in light of the vast technological opportunities for mass communication, the consequences for society and democracy will be broad and long-lasting.

The article was prepared by Sbunker as part of the project “Strengthening Community Resilience against Disinformation” supported through the Digital Activism Program by TechSoup Global.