I was raised thinking that the Balkans are the same people. In Serbo-Croatian-speaking countries, we often use the vague “we” (mi) and “or” (naši ljudi) to refer to shared aspects of our culture—language, traditions, music, or cinematography.

The term “Balkan” has always been another synonym for our ambiguous cultural identity. Acts of solidarity, such as the recent 15 minutes of silence observed by students of Croatian universities in memory of the 15 people who died in Novi Sad after the collapse of the railway’s canopy, or an additional 16th minute of silence held in in Belgrade for the child who died from a knife attack in Zagreb, ishin norma për mua., were the norm for me.

It took me time to realize and accept that, for many others in the Balkans, this sense of shared solidarity is far less common.

Since then, I have been asking myself how I missed this divide. Was I living in my bubble? I would be willing to accept I have lived in an illusion, but that illusion is reinforced every day of my life, by friends who live across the former Yugoslavia and the news and entertainment I consume.

This question came up again in August 2024, during my first visit to Kosovo.

Growing up, I had little connection to Kosovo. I often heard it mentioned in heated discussions full of strong opinions. In high school, I didn’t pay much attention to it either since the news was mostly sensationalist and focused on disasters.

Still, events like DokuFest and Anibar caught my attention, offering a rare and positive perspective that stayed with me.

Photo of Prizren by the author, Lazar Tripinovic.

I traveled to Prizren to attend DokuFest, Kosovo’s most popular film festival. I was expecting Kosovo to be a very different place, but once I was there it didn’t feel much different from other parts of the Balkans.

To be fair, Serbian and Albanian cultures are not a split image of each other. Yet, given the cultural diversity within both groups, which are themselves spread across multiple countries, nothing in Kosovo felt foreign to me.

Nevertheless, I did not experience the same empathy or connection with Kosovo as I do with other parts of the former Yugoslavia. I always believed in cross-Balkan solidarity, and suddenly, I felt like a hypocrite.

It was not just the lack of common identity or sympathy that caused this. I did not get a chance to become interested in Kosovo, because I would only get politically salient topics advertised to me, and those are not a reason to visit a place.

While I felt warmly welcomed by locals, many of whom spoke Serbian fluently, I was also overwhelmed by stories of ethnic tensions. I wanted to believe these tensions were just stereotypes to overcome, though I knew that healing would require more time and space.

After a joyful week at DokuFest, I came home with mixed feelings.

Kosovo made me reflect on our region as a collage of postmodern images—fragments we often ignore in Belgrade, just as we overlook everything beyond our city and our chosen summer spots on the Adriatic or Aegean seas.

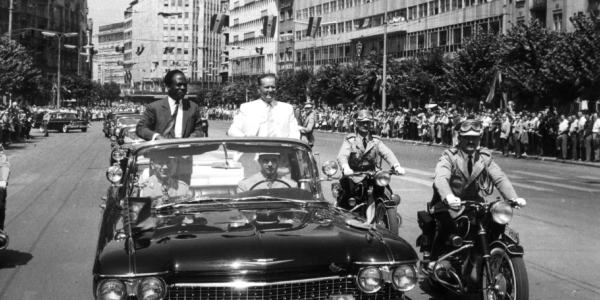

In Prizren, I was struck by the NATO monument nestled among oriental houses with small grocery stores and qebaptore. The Albanian and US flags tied together across a mosque vividly depicted Kosovars’ view of the past and their vision for the future.

On the way back to Belgrade, I passed through Prishtina and saw Bill Clinton’s statue, draped in a US flag, standing in front of a Yugoslav-era building.

This layering of narratives—where old heritage isn’t removed but stacked upon to fit new stories—is common in countries that have undergone radical change.

In Kosovo, as in Serbia, this creates a mosaic that could be seen as intriguing art but feels confusing as lived reality.

As I reflect on my journey in Kosovo, I keep wishing people understood that Kosovo is more than its ethnic tensions. Ethnic differences and conflicts aren’t the root of the problem, as we often believe.