Kosovo has made tremendous progress in its media landscape in recent years, continuously improving each year and providing citizens with more platforms for information, surpassing many countries globally and in the region.

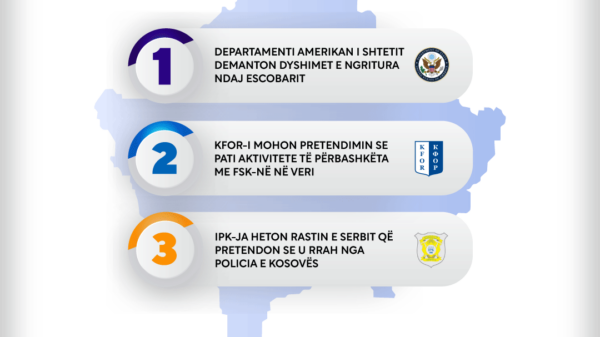

However, in May 2024, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) published their annual report on global media, ranking Kosovo at 75 out of 180 countries—a significant drop from 56th place in 2023. This 19-spot drop represents the largest recorded decrease in media freedom for Kosovo, with profound implications as the country approaches its parliamentary election.

This setback brings to the forefront the question: Does the abundance of media outlets ensure fair elections and accurate information for citizens, or does it merely flood the public with noise and confusion?

According to Xhemajl Rexha, the President of the Kosovo Journalists Association (AGK), “The last parliamentary election had been very chaotic because of so many debates, so many sources, so much noise. I'm not sure if the media helped Kosovo citizens get the right information.”

While media plurality and the variety of media sources are generally seen as positive, it can also be a double-edged sword. Marius Dragomir—Director of the Center for Media, Data and Society—observes, “An excess of sources doesn't always guarantee a healthier public discourse. Instead, it can lead to confusion, misinformation, or even the amplification of less credible voices, ultimately undermining the quality of democratic debate if not balanced with proper oversight and fact-checking.”

In an effort to assess the impact of media diversity, a colleague and I conducted a study after the 2021 election. We analyzed 100 randomly selected articles from Telegrafi and Kallxo, published between February 3 and 12, 2021. The findings revealed a notable absence of representation for civil society and the public in media election coverage.

If prominent media outlets such as Kallxo and Telegrafi fail to adequately represent diverse perspectives during elections, it is frightening to imagine the quality of election coverage in other local media outlets.

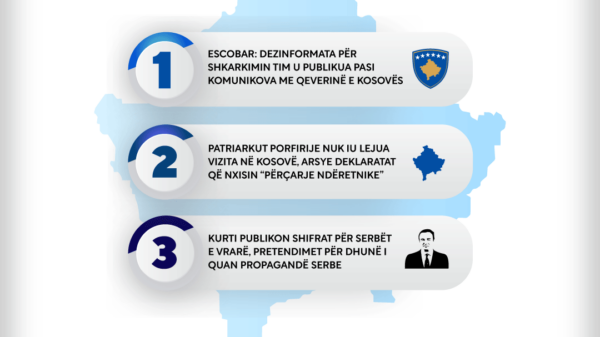

Foreign residents in Kosovo share similar concerns. Stefan van Dijk, a Dutch communications expert who has worked in Kosovo for a decade, recounts: “While monitoring election news on several portals, it was clear that some outlets made deliberate efforts to frame certain politicians or parties negatively.

He recalls one article that published a video showing different political candidates merely walking side by side during a rally. “The article claimed that Politician X pushed Politician Y behind him. I watched the video a couple of times, and it was clear that the road became narrower and that some politicians, because of that, had to move a little bit to the back. Absolutely nothing strange happened, but the article framed it like that,” stated van Dijk.

Kosovo’s media landscape, especially during elections, presents a complex interplay between political processes and media influence. While media plurality is often heralded as a cornerstone of democracy, its role in the 2021 parliamentary election suggests mixed results. Our study showed that much of the media focused on conflicts—campaign violations, personal attacks—rather than on substantive policy issues or the inclusion of civil society voices.

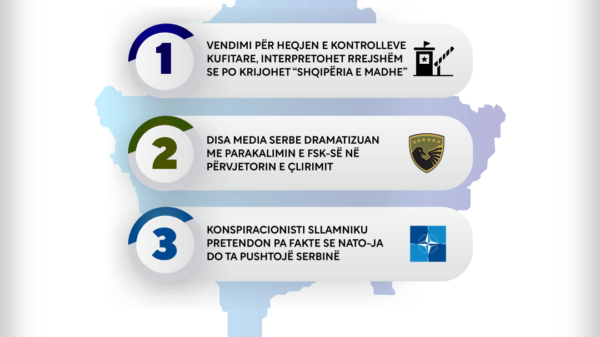

This tendency undermines the public’s ability to make informed decisions and signals deeper challenges in Kosovo’s democratic development. Allen Meta from Democracy for Development notes that “This shift towards conflict-oriented reporting, coupled with the rise of fake news and misogynistic rhetoric, can be attributed to the increased use of social media during the COVID-19 pandemic. Without in-person campaign events, political parties and media alike turned to online platforms, where sensationalism often trumps balanced discourse.”

On the other hand, Valdete Daka, former chair of the Central Election Commission, holds a more optimistic view, arguing that the majority of Kosovo’s media contributed to the fairness of the 2021 elections. According to Daka, “While some outlets exhibited political bias, most provided clear and equitable coverage of events.”

These contrasting views from public officials and civil society underline the ongoing debate about the media's role in Kosovo’s democratic development. The question remains: will the media’s relationship with the political system evolve into a mutually beneficial dynamic that fosters transparency, or will it continue to hinder democratic progress?

As Vetevendosje aims to retain power in the February 2025 parliamentary election, Kosovo’s media landscape and the RSF’s warning of declining press freedom could have serious implications. The deterioration of media freedom may obstruct citizens’ access to accurate information during both the campaign and the election itself.

While Kosovo’s media plurality might seem a positive development at first glance, a deeper look reveals several challenges. The prevalence of “copy-paste” journalism and the low standards of journalist education further threaten the quality of transparent reporting. These issues risk undermining voters’ ability to form informed opinions ahead of the upcoming election.