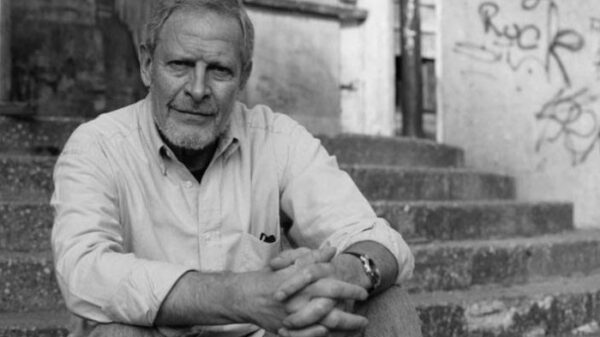

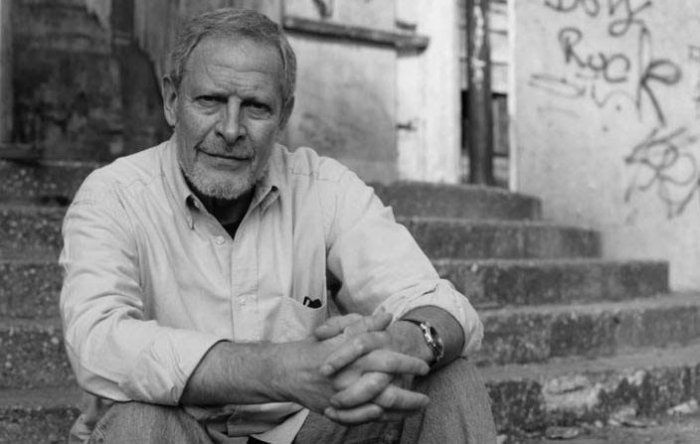

Photo by: Lazar Stojanović (1944 -2017), foto: CZKD

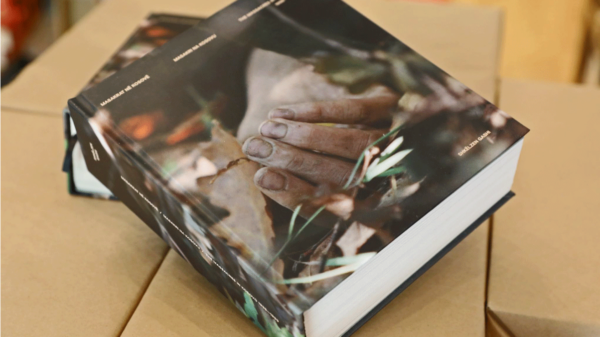

“The Other Serbia” project has compiled a collection of the thinking of Serbian intellectuals who opposed the Serbian authorities’ severe violations of the human rights of Albanians in Kosovo in the period from Serbia’s abolition of Kosovo’s autonomy, on 23 March 1989, to NATO’s entry into Kosovo on 12 June 1999, and later still.

“The Other Serbia” presents articles and interviews published over three decades in the daily press and weekly publications in Kosovo, Serbia and further afield. This volume includes excerpts from the articles and interviews of the most prominent of these intellectuals, the film director Lazar Stojanović [1944–2017], in which he talks about the brutal violation of the human rights of Albanians in Kosovo in the 1990s. In addition, we thought it was important to include excerpts in which Stojanović provides his views not only on the independence of Kosovo and its relations with Serbia, but also on the overall relations between Albanians and Serbs.

Lazar Stojanović stood out as one of the rare Serbian intellectuals openly criticizing the myth that Kosovo had been part of Serbia for centuries, even that Kosovo was its historical cradle. In Serbia, where discussing Kosovo was a taboo, and any critique was met with punishment, Stojanović fearlessly confronted enraged Serbian nationalists who sought reasons for conflict in the relocation of Serbs from Kosovo, urging them also to address the forced displacement of around 450,000 Germans from Vojvodina, a region now predominantly settled by Serbs. He cheekily added that if historical residence determined governance, Germans should be running Belgrade today, because of their earlier and more effective stewardship of the city.

Stojanović regarded Kosovo as a colony, a profound issue he learned about while serving a prison sentence as a dissident. During his imprisonment, he engaged in discussions with Albanian political prisoners, particularly Adem Demaçi. Stojanović was among the first voices in Serbia openly to oppose Serbia’s complete suppression of Kosovo’s autonomy during the ‘90s, which significantly curtailed the rights and freedoms of Albanians. He vehemently opposed the repression and segregation of Kosovo Albanians, asserting that they were being systematically held in ghettos.

In the wake of crimes committed by Serbian forces in late February and early March 1998 in the villages of Likoshan and Prekaz, Stojanović told the Serbian media in Belgrade that the Albanian people had endured a millennium of servitude. At the end of his statement, he appealed to the citizens of Belgrade, saying, ‘…let’s mitigate our shame by distancing ourselves from the crime.’

On the subject of Serbia’s crimes against Albanians in Kosovo in 1998 and 1999, Stojanović spoke of terrible killings, with particular emphasis on the massacre of children in the Bogujevci family in Podujeva by the Scorpions paramilitary unit, as documented in one of his films. He then discussed the destruction of property and the forced displacement of 850,000 Albanians, calling it a genocidal crime, especially as the goal was the ethnic cleansing of Albanians from the territory. He publicly expressed a desire to create a film documenting this mass deportation.

Stojanović pointed out that aviation and self‒propelled artillery were used during crimes against civilians, a clear violation of the rules of war. He held everyone involved accountable, from the person pulling the trigger to the general giving the order or failing to prevent it. Stojanović argued that even when crimes were committed by paramilitary units, regular army units were routinely used to isolate and secure the territory.

According to Stojanović, NATO’s intervention in 1999 divided the Serbian population into two groups: a minority who believed the decision to intervene was sensible and a majority who considered it unjust, anti‒Serb, and believed that Serbia had a right to Kosovo. He argued that the intervention took place primarily in Kosovo, where three‒quarters of the victims were killed, while the attacks in Serbia targeted only a few strategically important points to limit Serbia’s ability to wage war in Kosovo.

Stojanović empathized with every victim who fell as collateral damage from the bombings in Serbia, but he was unwilling to discuss it while there was nobody in Kosovo, where the majority of the victims were, who had an issue with NATO’s intervention. When asked if someone killed on the bridges of Serbia during intervention was a victim of genocide, he responded that they were not, as they were not killed because they belonged to a specific nationality but because they happened to be on the bridge. On the bombing of the building of Radio‒Television of Serbia, he defended the position that when a media outlet turns into an instrument of war that faithfully follows the pattern set by Goebbels, it becomes a legitimate target of war.

Stojanović assigned political and moral responsibility for the crimes committed in Kosovo not just to the Serbian political leadership but also to all those who supported Slobodan Milošević, aware that this included about seventy percent of the population at that time. He noted that around seventy percent of Germans also chose Hitler ‘democratically.’ Stojanović pointed out that Serbia had about ten or fifteen individuals who opposed its policy from the very beginning. While acknowledging this number was small, he stressed that these people existed. According to him, Milošević, through his criminal wars, caused great harm to neighboring peoples and states but also to Serbia itself. He viewed the availability of facts shedding light on events as crucial for achieving reconciliation, strongly opposing the notion that addressing these crimes was unpatriotic and that witnesses should be discouraged, blackmailed, or even threatened.

Stojanović not only endorsed Kosovo’s independence but actively and, to the best of his abilties, openly worked towards it from 1972. When Serbian politicians in Serbia insisted that Kosovo was Serbian, Stojanović reminded them that they could not control Kosovo, with a large Albanian majority and with just six percent of the population being Serb, without resorting to force. He stressed that the independence of Kosovo was irreversible, and according to him, everyone in Serbia knew this, no matter what they claimed.

Mocking the insertion of the provision in Serbia’s constitution stating that Kosovo is an inalienable part of its territory, Stojanović sarcastically suggested they could have also stated that the Earth is a cube. Moreover, he dismissed the idea as simply bizarre and ludicrous, with no consequences for the outside world. According to Stojanović, whoever put the idea that Kosovo as an inseparable part of Serbia into the Constitution didthe greatest disservice to the Serbian people and the political standing of Serbs and Serbia in Europe.

Following on from the studies of Bogdan Bogdanović, Miloš Minić, Srđa Popović and now Lazar Stojanović, forthcoming volumes of “The Other Serbia” project will include excerpts from articles and interviews of several other Serbian intellectuals, such as Bogdan Denitch [1929–2016], Ilija Đukić [1930–2002], Ivan Đurić [1947–1997], Mihajlo Mihajlov [1934–2010], Mirko Kovač [1938–2013], and others.

All these intellectuals were inspired by Serbian social-democrats such as Dimitrije Tucović, Kosta Novaković, Dušan Popović, Dragiša Lapčević, Triša Kaclerović, and others. Between 1912 and 1913, when Serbia occupied Kosovo, they opposed the horrendous crimes perpetrated by the Serbian state on the innocent civilian Albanian population there. An article by the social-democrat Tucović in the Belgrade socialist paper of the time, Radničke novine, illustrates this: “...we attempted a premeditated murder of a whole nation.” An editorial in the paper stated that it possessed data on crimes by Serb forces against the Albanians so horrendous that they chose not to publish them.

Unfortunately, these crimes were repeated: at the end of the World War I, in 1918 and 1919; then in the period between the two World Wars; at the end of the World War II (1944-1945); between 1946-1966; and finally in the last decade of the 20th century (1989-1999).

“The Other Serbia” project aims not only to offer examples of the intellectuals who opposed the crimes and injustices committed by state authorities led by their own ‘compatriots,’ whatever their justification, but also to honor the intellectual who puts his own life in danger by showing amazing courage that ought to receive well-deserved acclaim.

We hope that this publication will benefit journalists, political analysts and civil society activists who deal with Albanian-Serb relations; politicians involved in negotiations aiming to normalise these relations; students and academics; and the public at large. This also includes future generations in Kosovo, Serbia, Albania, and the Balkans.

Postwar Kosovo does not have a street, square or school named after the lawyer and humanitarian Lazar Stojanović, even though he strongly opposed the state terror of the Milošević regime at the start of the ’90s. Although he was the first and most vociferous intellectual who not only opposed the occupation of Kosovo by the Serbian regime but also supported the independence of Kosovo, the Kosovo Assembly failed to invite him to the ceremony of the Declaration of Independence on 17 February 2008.

Stojanović has contributed immensely to the protection of the human rights of Albanians in Kosovo, and to a peaceful and amicable solution between Albanians and Serbs, and their coexistence based on mutual tolerance and understanding.