“The Other Serbia” project has compiled a collection of the attitudes of Serbian intellectuals who opposed the severe violations of the human rights of the Albanians in Kosovo, by the Serb authorities, in the period from the abolition of Kosovo’s autonomy by Serbia, on 23 March 1989, up to NATO’s entry into Kosovo, on 12 June 1999, and even later. These violations reached their culmination in 1998 and 1999 with the killing of almost 10,000 Albanian civilians, the raping of thousands of women, the deportation or displacement of almost one million Albanians, and the burning and destruction of 100,000 homes, buildings, and heritage.

In “The Other Serbia” project, we have extensively researched articles and interviews published over three decades in the daily press and weekly publications in Kosovo, Serbia and wider. This volume includes excerpts from the articles and interviews of the lawyer Srđja Popović, the most prominent of these intellectuals, in which he talks about the brutal violation of the human rights of Albanians in Kosovo in the 1990s. In addition, we thought it was important to include excerpts in which Popović provides his views not only on the independence of Kosovo and its relations with Serbia, but also on the overall relations between Albanians and Serbs.

Srđa Popović was convinced that the Albanians of Yugoslavia had never integrated; they lived as a foreign body, and were treated as second-class citizens in daily communications, to the extent that even amongst children, the word “shiptar” was a derogatory word, similar to the American racist insult “nigger”. On the topic of relations between Albanians and Serbs in Yugoslavia, Popovic was one of the few Serb intellectuals who listed all the drivers of Serb displacement from Kosovo in the 1970s and 1980s, including: unemployment, poverty, over-population, and the challenge of communication among peoples of different cultures, faiths, and languages. At the end of Yugoslavia’s existence, he evaluated Serbia’s initiative to remove Kosovo’s autonomy within Yugoslavia as both anti-constitutional and an annexation of Kosovo from Serbia.

Popović considered Serb policy, at the end of the 1980s and throughout the 1990s, to be damaging because it created enemies for the Serb people, and not just in neighbouring countries. Furthermore, Popović considered Slobodan Milošević, the creator of this policy, to be the person who caused most harm to Serbia’s interests, and so he also criticized Serb citizens, who by supporting Milošević, were also seriously damaging the national interest. He was a harsh critic of the violation of the human rights of Albanians in Kosovo, by the Milošević regime, and he was aware of public opinion about Milošević in Kosovo, but he said that in the last ten years, the Albanians had passed through fifty years of history, and so, one day, they would raise a monument to Milošević, since he had helped them to become a nation that was both self-conscious and united, with internationalised demands.

Popović opposed the crimes against the Albanians of Kosovo, committed during the war by the Milošević regime, and he also opposed the two million people who voted for Milošević, whom he considered to be supporters of war crimes. According to him, those who denied the crimes committed by the Milošević regime against the Albanians of Kosovo were simply autistic. Popović supported the NATO intervention in Kosovo, but he thought that it was late. According to him, NATO intervention in Kosovo did not contravene international law and was useful for the Serb people, which needed a defeat in order to be revitalized.

Popović qualified the crimes of the Milošević regime toward Albanians in Kosovo as genocide because, according to him, just as there are different types of murder, so there are different types of genocide, and the genocide perpetrated by Milošević – which could not be compared to Holocaust only because he lacked the capacity for a crime of such proportions – fulfilled all the criteria that exist in the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, 1951. Given the terrible, mass crimes committed against the Albanians, he expressed understanding of the revanchism of the Albanians, which was mostly against the Serb minority in Kosovo, in the period of June to December 1999.

Definitively, Popović is one of Serbia’s greatest patriots, and this quality is made clear by the following declaration: “I am not saying it is a good thing that Kosova is independent, but something exists that is called reality, and we should not deceive ourselves, just because we do not like this reality.” He even said that those who accept an independent Kosovo are honorable, courageous patriots. Above all, Popović’s patriotism is visible is his position that it is in the interest of the Serb people not to be identified with the policies of Milošević, not to have to bear this historic mortgage forever, which he clearly states here: “One day when they say, ‘you Serbs kept silent when these things were happening’, you can feel free to say that there were also people who didn’t remain silent, who spoke out.”

Following on from the studies of Bogdan Bogdanović, Bogdan Bogdanović [Bogdan Bogdanović], Miloš Minić and now Srđja Popović, forthcoming volumes of “The Other Serbia” project will include excerpts from articles and interviews of several other Serbian intellectuals (which although few, still do exist), who are unfortunately no longer amongst the living, such as Bogdan Denitch [1929–2016], Ilija Đukić [1930–2002], Ivan Đurić [1947–1997], Lazar Stojanović [1944–2017], Mihajlo Mihajlov [1934–2010], Mirko Kovač [1938–2013], and others.

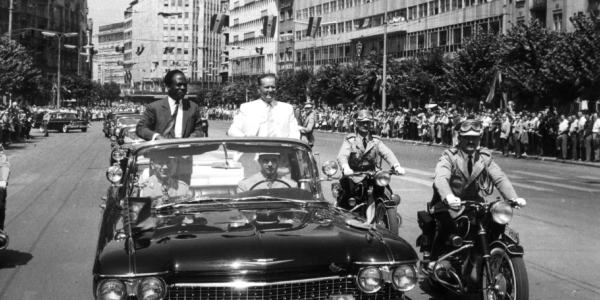

All these intellectuals were inspired by the Serbian social-democrats such as Dimitrije Tucović, Kosta Novaković, Dušan Popović, Dragiša Lapčević, Triša Kaclerović, and others. Between 1912-13, when Serbia occupied Kosovo, they opposed the horrendous crimes perpetrated by the Serbian state on the innocent civilian Albanian population in Kosovo. An article by the social-democrat Tucović in the Belgrade socialist paper of the time, “Radničke novine”, illustrates this: “...we attempted a premeditated murder over a whole nation”. An editorial article of the paper stated that it possessed data on crimes so horrendous by Serb forces against the Albanians, that they chose to not publish them. Unfortunately, these crimes were repeated at the end of the World War I, in 1918 and 1919, then in the period between the two World Wars, at the end of the World War II (1944-1945), between 1946-1966, and finally in the last decade of the 20th century (1989-1999).

“The Other Serbia” project aims not only to offer examples of the intellectuals who opposed the injustices and crimes committed by state authorities, led by their own ‘compatriots’, and regardless of the justification, but also to honour the intellectual who endangers his own life by showing amazing courage that should receive deserved acclaim. Unfortunately, these personalities were viewed by large sections of the Serbian nation as traitors and were judged, branded, defamed, and attacked. Among the Albanians, they were viewed with mistrust and disregard.

We hope that this publication will benefit journalists, political analysts and civil society activists who deal with Albanian-Serb relations; politicians involved in negotiations aiming to normalise these relations; students, academics and the public at large. This also includes future generations in Kosovo, Serbia, Albania, and the Balkans, as well as those interested throughout the world. The project will be published online in Albanian and Serbian, and English.

Postwar Kosovo does not have a street, square or school named after the lawyer and humanitarian Srđja Popović, even though he strongly opposed the state terror of the Milošević regime at the start of the ’90s. Although he was the first and most vociferous intellectual, who not only opposed the occupation of Kosovo by the Serbian regime, but also supported the independence of Kosovo, the Kosovo Assembly failed to invite him to the ceremony of the Declaration of Independence on 17 February 2008.

Hence, let this publication be a modest recognition of the great contribution of this extraordinary intellectual, for his defense of the human rights of Albanians in Kosovo, and for his contribution toward a peaceful and amicable solution between Albanians and Serbs, and likewise their coexistence based on mutual tolerance and understanding.

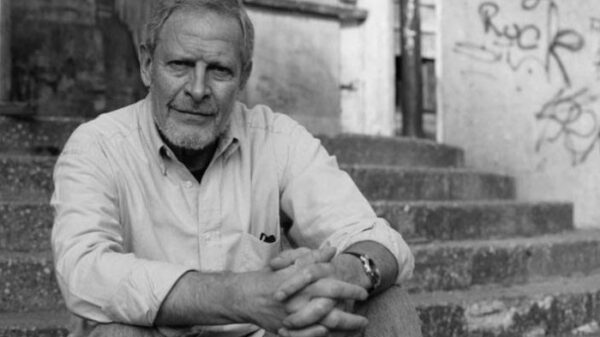

Srđa Popović (1937-2013)

He was born in Belgrade in 1937. He studied law at the Law Department of Belgrade University. He worked as a human rights lawyer, defending activists and academics who were being persecuted for opposing the communist regime in Yugoslavia. His various cases included defending the protesting students and professors of 1968, in Belgrade, as well as Albanian student demonstrators in 1981, in Prishtina. One of the slogans shouted at the 1968 protest was ‘Walls, walls, I’m sitting in a jail cell, call Srđa the lawyer to get me out of this hell’ – which indicated that by then he had become the leading human rights lawyer.

In 1976, he was sentenced to one year in prison for sharing the same opinion as his client, the poet and dissident, Dragoljub Ignjatović. Some weeks later, after a request made by 106 respected American lawyers to Josip Broz Tito, then president of Yugoslavia, he was released from prison, but he was banned from exercising his legal profession for one year. During his career, he also defended people with whom he did not agree at all, arguing that each person had the right to freedom of expression and to a fair trial.

After the arrival of Slobodan Milošević in power, he was among the first to openly criticize his repressive politics. He was the chairman of the Independent Commission for the Investigation of the Exodus of the Serbs from Kosova, where he dismissed the claims of the Serbian regime that the so-called departure of Serbs from Kosova was the result of the violation of their rights. At the start of 1990, he founded the weekly newspaper, ‘Vreme’, in response to the instrumentalism of the Serb media by the Milošević regime. Later, he was elected President of the European Movement in Serbia.

In 1991, he migrated to the US to work, partially due to the political climate under Milošević’s rule. He served as a member of the advisory board of various international organizations for the protection of human rights, such as the Helsinki Committee, and Amnesty International. In 1993, he was among the signatories of a petition calling on the US president, Bill Clinton, to intervene against Serbia’s actions in Bosnia. Similarly, in 1999, he supported the NATO bombing of Serbia to stop ethnic cleansing in Kosovo.

After about a ten-year stay in the USA, and after the removal of Milošević from power, he returned to Belgrade, where he was a harsh critic of the failure of the Serbian government to take responsibility for the crimes committed during the 1990s. He is the author of five books. He died in 2013 in Belgrade.